This is a sermon I preached at Open Way Community Church on Sunday, Dec. 8, 2019.

A reading from Matt. 2:13-23

13 When [the Magi] had gone, an angel of the Lord appeared to Joseph in a dream. “Get up,” he said, “take the child and his mother and escape to Egypt. Stay there until I tell you, for Herod is going to search for the child to kill him.”

14 So he got up, took the child and his mother during the night and left for Egypt, 15 where he stayed until the death of Herod. And so was fulfilled what the Lord had said through the prophet: “Out of Egypt I called my son.”[c]

16 When Herod realized that he had been outwitted by the Magi, he was furious, and he gave orders to kill all the boys in Bethlehem and its vicinity who were two years old and under, in accordance with the time he had learned from the Magi. 17 Then what was said through the prophet Jeremiah was fulfilled:

Flight into Egypt by James Tissot, 1880s.jpg

18 “A voice is heard in Ramah,

weeping and great mourning,

Rachel weeping for her children

and refusing to be comforted,

because they are no more.”[d]

19 After Herod died, an angel of the Lord appeared in a dream to Joseph in Egypt 20 and said, “Get up, take the child and his mother and go to the land of Israel, for those who were trying to take the child’s life are dead.”

21 So he got up, took the child and his mother and went to the land of Israel. 22 But when he heard that Archelaus was reigning in Judea in place of his father Herod, he was afraid to go there. Having been warned in a dream, he withdrew to the district of Galilee, 23 and he went and lived in a town called Nazareth. So was fulfilled what was said through the prophets, that he would be called a Nazarene.”

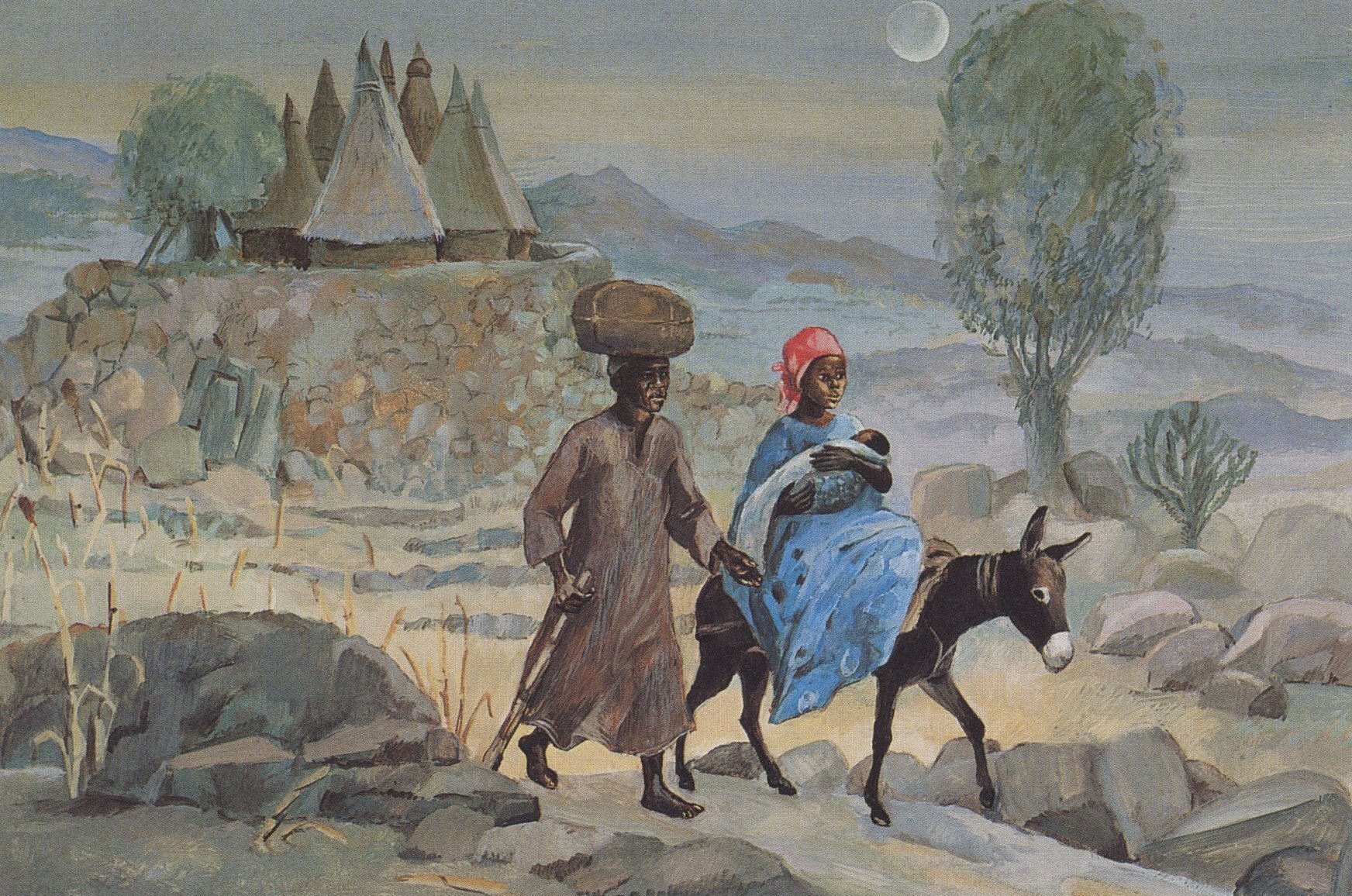

Kim Yong Gil, Flight To Egypt, 1990

“May You Find A Light”

(David Gungor)

Lost and weary traveler,

Searching for the way to go

Stranger, heavy-hearted,

Longing for someone to know

May you find a light

May you find a light

May you find a light to guide you home.

There are weary travelers,

Searching everywhere you go

Strangers who are searching,

Longing deeply to be known

May you find a light

May you find a light

May you find a light to guide you home.

There are weary travelers searching everywhere you go.

You can dig through the dirt of any country,

through the generations, through the memories,

and unearth story after story of weary travelers, longing for home.

This is the final week in our series about welcoming the stranger,

and seeing scripture through the lens of refugees and immigrants.

So I want open this sermon by telling you a few refugee stories I’ve come across.

Some names have been changed for protection.

Interspersed in the stories, I’ll include some stanzas

from Warsan Shire’s poem entitled “Home,”

S Sudjojono, Flight to Egypt, 1985.

Rahel lived in the Middle East.

Rahel and her husband Yaqub had several children.

But still Rahel longed prayed for another.

She gave birth to Yusuf.

Yusuf was his parents’ favourite.

Yusuf loved to wear dresses.

Yusuf was a dreamer –

he liked to talk about his God-given dreams.

Yusuf wasn’t well loved by his siblings, to say the least.

When he was 17, they threw him in an empty well.

They sold him to slave-traders.

They told his parents he was dead.

Rahel and Yaqub wept and wept, and would not be comforted.

i want to go home,

but home is the mouth of a shark

home is the barrel of the gun

and no one would leave home

unless home chased you to the shore

Yusuf marched days and nights through the desert

and found himself in Egypt,

overcome with homesickness, recognizing nothing,

dreaming of being understood and truly seen by someone.

But Yusuf the Dreamer was resilient.

Slowly he learned the culture, the customs, the language.

God watched over him, and he made a life there.

And when his brothers became the refugees,

desperately fleeing the famine that ravaged their homeland,

Yusuf became their savior, their rescuer,

welcoming them into Egypt, land of refuge.

Flight into Egypt, Jesus Mafa, 1973

the go home blacks

refugees

dirty immigrants

asylum seekers

sucking our country dry

niggers with their hands out

they smell strange

savage

messed up their country and now they want

to mess ours up

how do the words

the dirty looks

roll off your backs

maybe because the blow is softer

than a limb torn off

Let me tell you about Musa.

Musa, like many refugees, had the great misfortune

of being born under the shadow of violent ruler

who himself was ruled by fear.

Fear especially of those “dirty immigrants, sucking his country dry.”

Fear that led him to enslave those immigrants,

and to order the murder of their baby boys, boys like Musa.

There were those who resisted.

God whispered to the midwives of Musa’s country –

brave allies from outside God’s people –

and they quietly refused to comply.

So Musa was not killed at birth.

Musa’s mother kept him hidden for as long as possible,

but babies are uncooperative hiders.

Desperate, she put her son in a basket and floated him down the river.

Nicholas Mynheer, Flight to Egypt, 2004

you have to understand,

that no one puts their children in a boat

unless the water is safer than the land

no one burns their palms

under trains

beneath carriages

no one spends days and nights in the stomach of a truck

feeding on newspaper unless the miles travelled

means something more than journey.

Musa was plucked out of the river

by the king’s daughter.

Musa, crying in the basket, moved her to pity.

She wanted to keep him.

Musa had an older sister who was hiding nearby,

watching what happened.

Her name was Maryam.

Maryam was a quick thinker, and asked the king’s daughter

if maybe she needed help nursing the baby –

Maryam knew just the woman to do it.

So Musa was raised by his own mother

as he prepared to live in the palace of his people’s oppressors.

And from that place of privilege, when the time was right,

Musa became his people’s savior, their rescuer,

leading them out of Egypt, land of slavery.

Eugene Derardet, Flight to Egypt, 1853.

and no one would leave home

unless home told you

to quicken your legs

leave your clothes behind

crawl through the desert

wade through the oceans

drown

save

be hunger

beg

forget pride

your survival is more important

We keep digging in the dirt,

we find another layer to excavate for stories.

‘Iiramia was a lot like Yusuf, from our first story.

Not very popular, because he liked to rant and rave about the future.

‘Iiramia was known as the weeping prophet.

He knew that he knew that destruction and war were coming.

‘Iiramia tried to warn his people,

but it was too late.

They were besieged by their enemies.

Many died in the battle, and ‘Iiramia watched in a city called Ramah

as families were rounded up and taken captive.

In his devastation, ‘Iiramia let his mind wander back,

and he pictured our friend Rahel, his ancestor, his people’s matriarch,

who was surely weeping again for her children,

as she had once wept for her lost child Yusuf,

refusing to be comforted, for they were gone.

The Flight Into Egypt, for Liturgy, Natalia Goncharova, 1915

no one leaves home unless

home is the mouth of a shark

you only run for the border

when you see the whole city running as well

your neighbors running faster than you

breath bloody in their throats

the boy you went to school with

who kissed you dizzy behind the old tin factory

is holding a gun bigger than his body

you only leave home

when home won’t let you stay.

‘Iiramia’s people marched for days and nights through the desert,

and found themselves in Babylon.

Overcome with homesickness, recognizing nothing,

they said, “How can we sing the songs of the Lord in a strange land?” (Ps. 137:4)

So ‘Iiramia passed on this message from God to his people:

”Build houses and settle down.

Plant gardens.

Marry. Have children.

Seek the peace and prosperity of this city where you have been taken in exile.” (see Jer. 29:5-7)

So the people learned to be resilient.

Slowly they learned the culture, the customs, the language.

God watched over them, and they made a life there.

And when a new king came to power,

he became their savior, their rescuer,

sending them back to the place they had once called home.

I have one final layer of story to excavate.

This one is difficult, because it has so many threads attached.

Some call them prophecies and fulfilments.

They’re running to the layers above and below, before and after,

and we don’t want to accidentally sever one of them.

We come to a place called Bethlehem, and find Maryam.

Attached to her name is a root running back to that quick-thinking sister

who once protected a threatened baby named Musa.

Holy Family Icon by Kelly Latimore, 2018

And we find her new husband Yusuf.

Attached to his name

is a root running back to that ancient dreamer

who saved his family by bringing them to Egypt.

And we come to their son, Isa,

barely 2 years old now,

who had the great misfortune

of being born under the shadow of violent king

who himself was ruled by fear.

This king was infamous

for having his own sons executed for “treason.”

When he heard that Isa might be the chosen one,

the true king of the Jews,

He ordered the murder of all baby boys around Isa’s age

in Bethlehem.

The roots here run deep, we find echoes of past horrors.

no one leaves home until home is a sweaty voice in your ear

saying-

leave,

run away from me now

i dont know what i’ve become

but i know that anywhere

is safer than here

So again, we hear the matriarch Rahel weeping.

(Rahel’s tomb was less than a kilometer from Bethlehem.)

She grieved yet more children with lives cut short.

There were those who resisted.

God whispered to the magi –

brave allies from outside God’s people -

and they quietly refused to comply with the king.

In a way, they midwifed baby Isa,

bringing his family provisions.

God also whispered to Yusuf, sending him dreams,

just like his namesake,

telling Yusuf to run, no time to pack,

leave now, in the night,

follow that path through the desert along the sea,

a 500-kilometer road,

well worn by now from all the weary travelers,

the back and forth along the road to Egypt,

that ancient place of slavery, place of refuge,

place that is not home.

no one leaves home unless home chases you

fire under feet

hot blood in your belly

it’s not something you ever thought of doing

until the blade burnt threats into

your neck

and even then you carried the anthem under

your breath

only tearing up your passport in an airport toilets

sobbing as each mouthful of paper

made it clear that you wouldn’t be going back.

Yusuf’s family marched days and nights through the desert,

until they found themselves in Egypt.

Overcome with homesickness, recognizing nothing.

Maryam barely 15, taking care of a toddler.

Yusuf the carpenter, stuck in a land of palm trees, no wood to work with,

forced to look for day work, to sell the gifts the Magi had given, to beg.

But Yusuf and Maryam were resilient.

Slowly they learned the culture, the customs, the language.

God watched over them, and they made a life there.

Andrzej Pronaszko, Flight to Egypt, 1921

Until Yusuf was given another dream,

and saw that the wicked king

who threatened his child was dead.

Yusuf, Maryam and Isa would re-enact

their people’s famous journey out of Egypt,

but this time they would not return

to the promised land, to their home.

Another dream warned them the new ruler,

the king’s son, was just as violent.

They settled in Nazareth, in Galilee,

a place filled with foreigners

and looked down upon by most Jews.

When I tell this story,

I wonder why God didn’t intervene

to save all the other boys in Bethlehem.

Could God not have given warning dreams

to those other 20-100 families, as well?

Of course, there will be a time

only 30 years later in the story

when God will choose not to intervene to save Isa, either.

And for that reason, Isa, once the refugee toddler,

once the kid from the backwater town,

will become the new Musa of a new Exodus,

the Savior and Rescuer not just of Israel, but of all peoples.

leading them out of their slavery to death, and into life.

Leading us all home.

------

John August Swanson, Flight Into Egypt, 2002

Rahel, Yaqub, Yusuf, Musa, Maryam, ‘Iiramia, Isa…

Obviously I changed their names

not for their protection,

I translated them into Arabic to protect us

from our overfamiliarity with the scriptural stories.*

Names like Rachel, Jacob, Joseph, Moses,

Mary/Miriam, Jeremiah...

those names sound a little too much like my own.

It’s all too easy to picture them

as white middle-class suburbanites.

It’s all too easy to let the centuries

and the influence of my white Christianity

drift their stories too far toward mine,

and too far removed

from the stories of the 26 million refugees

who fled their homes last year,

25 people for every minute of that year,

most of whom look nothing like me.

Half of those 26 million refugees last year

were child refugees, like Jesus was.

Their earliest memories were hearing their parents’ fearful warnings

not to play outside, to say nothing, to stay hidden.

followed closely by memories

of their father’s barely-perceptible tears,

the circles under their mother’s eyes,

eating unfamiliar food,

and hearing a strange language

spoken all around them.

This is not how we like to imagine

Jesus’ birth and childhood.

Especially at this time of year

when we crave the cozy familiarity of the story.

No one wants a Herod in their snow-globe,

or to be startled by screams

in the middle of a candlelit carol.

This is kind of a downer of an Advent sermon.

And what’s more,

no one wants a God who runs scared.

No one wants a God begging at the border

to be spared.

A God with bare and frozen skin,

utterly dependent on the mercy of foreigners,

a God needing to be rescued

before that God can rescue us.

Our world worships

the ones who stand their ground,

who won’t be moved,

who are strong enough to fight back.

But this God does not come

with armies or even shields.

This God knows violence is the failure of Love,

and this God is love.

This God needs to be Emmanuel,

the God who is profoundly with us,

and who is profoundly with those I call “them.”

Which means this God will come

as an undocumented child refugee

seeking asylum from the death squads hunting him.

I need to be startled by Isa the refugee,

to learn to see the face of God in the face of the one so unlike me.

Yet there is a danger I see in talking about Jesus the refugee,

and sharing biblical refugee stories.

The danger is that I will believe that refugees today

need to have Christlike, Bible hero innocence

to be worthy of my compassion or help.

Refugees; Holy Family by Kelly Latimore, 2018

The danger

is that will still make a mental distinction

between the “good” refugees like Jesus,

the sinless, childlike lambs

running from certain death,

and the so-called “bad” ones,

who perhaps did things they now regret

in order to survive,

who have not followed all the rules

or waited long enough or checked all the boxes.

The complicated refugees.

The human refugees.

To avoid that danger, here’s what I need to do...

I need to take my safe, overprotected, white middle-class story

and search for the threads that connect to these ancient and modern refugee stories,

however weak or loose those threads might be.

I need to connect my story to theirs, to see how we ARE alike,

NOT in any way to equate my pain to theirs, or to say “I know how it feels,”

but in order to equate my humanity with theirs.

We need to walk in the knowledge that each of us could have been refugees,

that most of us did not choose

to be born or brought

to this country of relative stability.

And that even this Canadian stability is not guaranteed forever.

In the words of Benjamin Zephaniah,

Flight into Egypt by Mabel Royds, 1938

“All it takes is a mad leader

Or no rain to bring forth food,

We can all be refugees

We can all be told to go,

We can all be hated by someone

For being someone.”

And if we were refugees, or if we ever are,

we will all bring our full humanity,

along with all our mistakes and vulnerabilities

... and we would still be worthy of protection.

If you know your Bible, you know

there is no such thing as Bible hero innocence

and that there are details I didn’t include in my earlier stories

for example, how Yusuf, Joseph,

had an enormous ego,

and how Moses carried the shadow

of having committed murder.

We need to work to see the complexity of our common humanity

and the “nevertheless” reality of the image of God in all of us.

The resulting empathy might just move us to deeper compassion

at our borders, at our detention centers.

It might move us to find a light to guide them home.

So as we close, I invite you to tether your imperfect human stories

to the ones I’ve excavated today, and to the millions of refugee stories

currently in progress around the world, even in our own city of Vancouver,

by asking yourself these questions along with me:

Erland Sibuea (Indonesia), Flight To Egypt

When have I felt trapped or unwelcome?

When has home not felt like home?

When have I left behind family, friends,

or other sources of security?

When have I been forced to venture

into the unknown?

When have I felt defenseless? Homesick? Unseen?

When have I arrived in an unfamiliar place

and wondered if God was still with me?

What aspects of these parts of my story

do I regret?

Who have been my unlikely allies? My saviors?

Can I imagine even a sliver

of a refugee experience?

Can I see our common humanity?

Even as we dig through the layers, as we follow the threads,

through the generations, we also uncover present-day refugee stories -

finding so many homes destroyed,

so many weary travelers trekking through the wilderness,so many children who do not survive,

so many mothers weeping like Rachel,

And we see scared little king Herod, followed by another scared little king Herod,

each wielding too much power for their own good,

death squads and armies and nuclear weapons at their fingertips.

Yet for all their threats and senseless murders,

they cannot prevent leaders of love from rising from the ash.

I want to close with a word of hope.

These verses are taken from the book of Jeremiah

directly after the verses quoted in today’s passage

about Rachel weeping for her children.

They’re words from our Refugee God

for every weary traveler trying to find the light to guide them home:

Rest on the Flight Into Egypt, Luc Olivier Merson, 1879

“Restrain your voice from weeping

and your eyes from tears,

for your work will be rewarded,”

declares the Lord.

“They will return from the land of the enemy.

So there is hope for your descendants,”

declares the Lord.

“Your children will return to their own land.”

(Jer. 31:16-17)

* I’m indebted to this article for the idea of translating the biblical names into Arabic.