Not long ago, I read a blog that raised an interesting question: why do Christians and churches in North America tend to give more to the poor overseas (especially to Africa and to places where natural disasters have occurred) than to the poor in their own cities?

Robb Davis, the writer of the blog I read, thinks it has very little to do with the fact that overseas poor people are poorer than our poor people. He thinks it has more to do with the fact that we generally see overseas poor people as deserving, and our own poor people as undeserving, or at least less deserving. I tend to agree.

Whether or not we care to admit it, I think we all have a subconscious scale of who really deserves our help (money, mission trips, prayers, attention). It probably looks something like this:

MOST DESERVING

Children born into poverty in third-world countries

Victims of natural disasters

Adults in third-world countries

Prostituted women in other countries, trafficked into North America

Children born into poverty in North America

Adults in North America who have lost their jobs due to the recession

Adults in North America who have never had stable jobs

Prostituted women born in North America

Drug addicts

Drug dealers and other criminals

Sex offenders

LEAST DESERVING

Ok, maybe that list is splitting hairs a bit. But I do think we have this natural tendency to decide who deserves our help based on how much we think their choices led them into their circumstances, that is to say, based on how much we think their poverty is their fault.

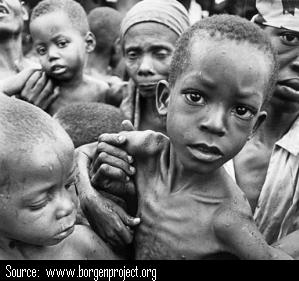

Children in Africa definitely didn't choose to be born into malnourished, war-torn environments where they will receive little education and few opportunities. We have no qualms about helping them. Natural disasters are nobody's fault (or the developed world's fault, if you consider climate change), so we're definitely supposed to help those people. Trafficked women were kidnapped or tricked into prostitution, so they're deserving - the worst we could accuse them of is naivete.

But prostitutes in my neighbourhood? The popular opinion is that they're choosing to do that work. And probably choosing it because they need to fund their drug addictions, and it's their fault that they're addicted. No one forced them to do drugs. And look at all the social assistance programs and advantages they have! They get an education and plenty of opportunities like everyone else in North America. So if they're still poor, obviously they lack initiative; they're just working the system, choosing to remain poor and taking welfare money from hard-working middle class people. Why would we enable their bad choices by giving them more hand-outs?

This sounds harsh, and most of us don't go that far in our thinking, but believe me, when I am dumb enough to read the comments on online news articles about the DTES, I see far more scathing opinions about the poor people in my neighbourhood.

I have begun to learn the real meaning of "choice" in the midst of the oppressive and degrading structural inequity that most people in my neighbourhood face. Just this week I met a woman, who has likely been prostituted, in recovery for her addiction, using our hard-earned tax dollars. She shared with me that she had been in twenty-four different foster homes over the course of her life. Yes, she got an education... in fourteen different schools. "Never really fit anywhere," she said. No kidding. The choices she has had to make and odds she has overcome just to get into recovery far outweigh any of my good life choices as a middle-class, stable-familied Masters-educated white girl.

So in light of this, who deserves our help? Who deserves our love? Who deserves our self-sacrificial giving?

In her book "Jesus Freak," Sara Miles tells a story about hosting a group of grade four kids at her church's food pantry program, and some of the questions they raised. They were concerned that some people who came to get food didn't really need it, or were cheating and taking too much. Like many adults, these kids didn't want anyone to take advantage of the church's generosity. Here's what Sara writes:

"I talked with the kids about the idea of “taking advantage,” explaining that it was impossible to be taken advantage of as long as you were giving something away without conditions. “If it's a trade, than it's fair or unfair,” I said. “But if I'm going to give it to you anyway, not matter what you do, then you can't take advantage of me.”

“How many of you have ever taken the best piece for yourself, or stolen something?” I asked, raising my own hand. Slowly, every hand went up.

“How many of you have ever been generous and given something away?” Every hand went up.

“Yeah,” I said, “You know, poor people cheat and steal and are really annoying. Just like rich people. Just like you. And poor people are generous and kind and help strangers. Just like rich people. Just like you.... In my church, we say that judgment belongs to God, not to humans. So that makes things a lot easier for us. We don't have to decide who deserves food.” (37)

I think Sarah Miles is on to something here. All of us do beautiful things and awful things, simply by virtue of being human. Yes, poor people in Canada cheat and steal. Poor people in Africa also cheat and steal, as I just confirmed in a conversation with a friend of mine who works in Darfur. Regardless of nationality, people who have been repeatedly abandoned and betrayed by others get used to cheating and stealing to survive. And yes, rich people cheat and steal, in ways that are often rewarded by society. All of us are sinners and letdowns, even the "noble" poor in the World Vision commercials. It's just that we're close enough to the poor in Canada to see their shadow sides. And they're close enough to make us feel very uncomfortable and guilty, and we can't just change the channel to push them out of our view.

Now, I do think we need to think carefully about the ways we try to help the poor, whether they're here or overseas, because our methods can often decrease their dignity and self-worth and increase their predisposition to want to cheat the system. Peter Maurin, a good friend of Dorothy Day's, said that we need to strive to make the kind of society in which it is easier for people to be good. This is a society in which we assume the best of one another, strive to see the image of God in one another, draw out each other's gifts and skills, love each other unconditionally over the long term, and uphold each other's dignity. In that society, no one will want to cheat the system, because they will belong; they will know they are needed, and they will have what they need.

This past Wednesday night at our worship service at Jacob's Well, a friend of mine did something that is really quite strange. She drew a cross on my forehead with ashes and told me that I was made of dust, and that one day I would die. She did the exact same thing to everyone in the circle, all of us, rich and poor... all of us bags of ashes and water, all of us sinners and sinned-against, all of us selfish screw-ups... all of us unable to be good on our own, unable even to sustain our own lives... all of us undeserving...

...all of us created in the image of God, the grateful recipients of unearned and undeserved grace, of each new day and each next breath...all of us empowered and sent to care for one another and to share with one another and to be healed and sanctified together.

So, all of us - let's share what we have with everyone who needs it, in Africa, in Japan, in Canada, in the DTES, whether or not we think they deserve it. And let's love each other so much that we want to be better people, in the knowledge that we'll never be good enough to deserve the love and grace God seems to want to keep lavishing on us.